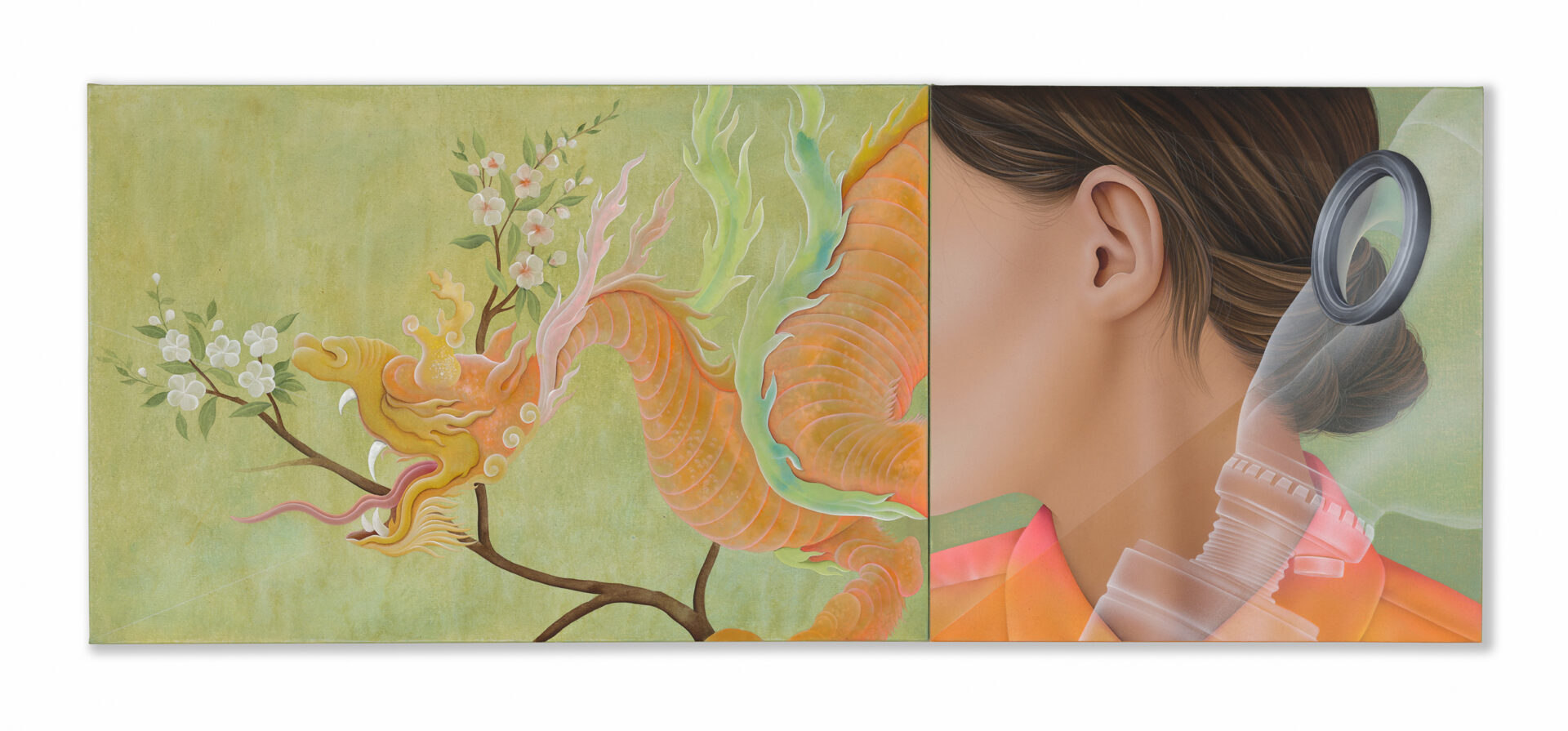

“Memories of Iran”: Arghavan Khosravi muses on Newport Art Museum exhibition

By Helena Touhey

For Arghavan Khosravi, an artist born and raised in Iran, painting is as much a means of coping with unsettling events as it is a form of dialogue around the freedoms of women

At the opening reception for Arghavan Khosravi’s current exhibition at the Newport Art Museum, a woman came up to the artist and expressed her admiration, specifically noting how the pieces retained a sort of softness and vibrancy despite the heaviness of their subject matter.

Khosravi thanked the woman for sharing this interpretation. The mix of heavy and softness in her work is at least partly intentional: With each piece, she hopes to convey the push-and-pull of tension rooted in restriction, which is personal to her experience growing up in Iran, where life in private was much different than life in public. It is also reflective of a more universal sentiment of oppression that anyone can relate to or understand.

“If the paintings are too dark, both in terms of the concepts and also how they look, I myself, as the painter, cannot stand working on them,” Khosravi elaborated a few weeks later, during a phone conversation, her voice soft and words thoughtful. “I need to find a balance between beauty and the not-so-pleasing concepts beneath that colorful surface.”

The artist was born in the wake of the Iranian Revolution, and her formative years were shaped by life under the regime of the Islamic Republic of Iran. In public, Islamic laws had to be observed, whereas in private, life was lived more freely.

“The main subject matter in my work, which is reflecting on my memories of Iran, is the situation in Iran mostly for women,” she says. As a young woman, Khosravi, who was raised in a non-religious family, was once arrested while walking down a street in Tehran because her hijab did not cover enough of her body.

More recently, the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement has gained momentum in the last year-and-a-half, following the beating and murder of Jina “Masha” Amini, a 22-year-old woman who was taken into custody by the Iranian morality police for not wearing her hijab properly.

“The act of painting itself, for me, is a way to cope with these traumatic events which I have experienced back in Iran,” and which she continues to hear about on the news or from friends and family, Khosravi says. She left Iran in 2015, at the age of 30, to attend a post-baccalaureate program in studio art at

Brandeis University.

“The very first reason I paint is because it makes me feel good,” she says, describing the act as therapeutic or healing.

“And then when I share [my work] with other people, it creates a larger dialogue around those issues or similar issues that people from different life experiences have,” she adds. “I use a lot of symbolism in my work, and that also helps, so that the paintings can be interpreted by different viewers that are coming from different walks of life.”

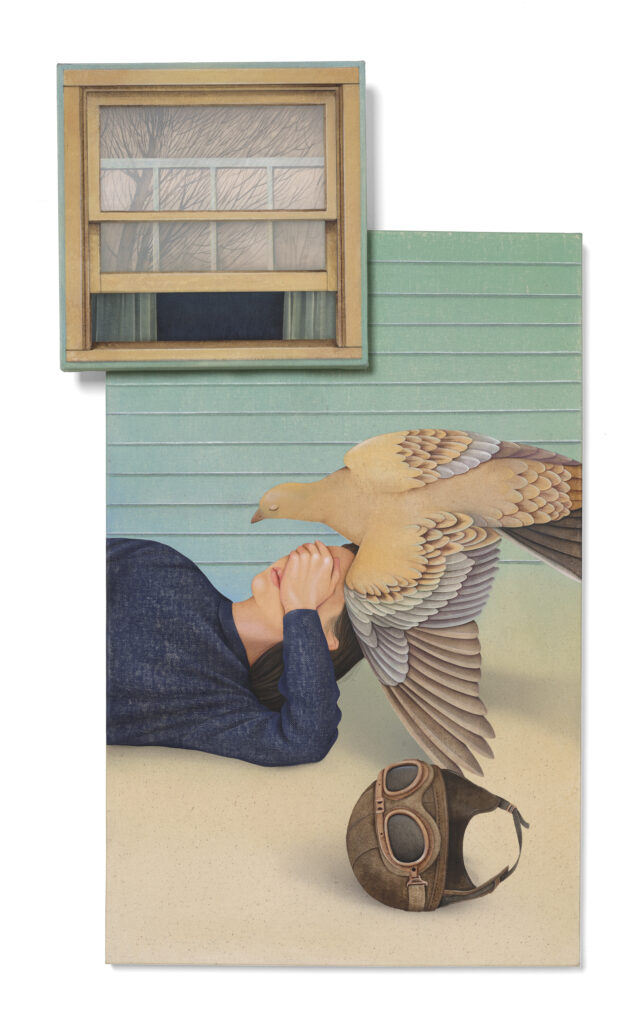

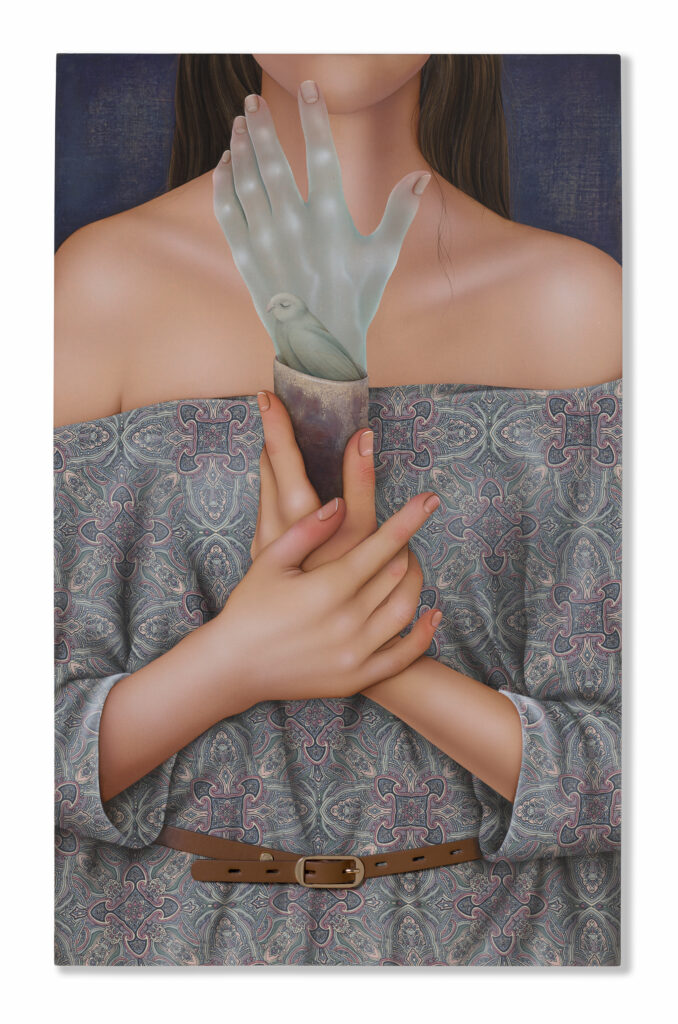

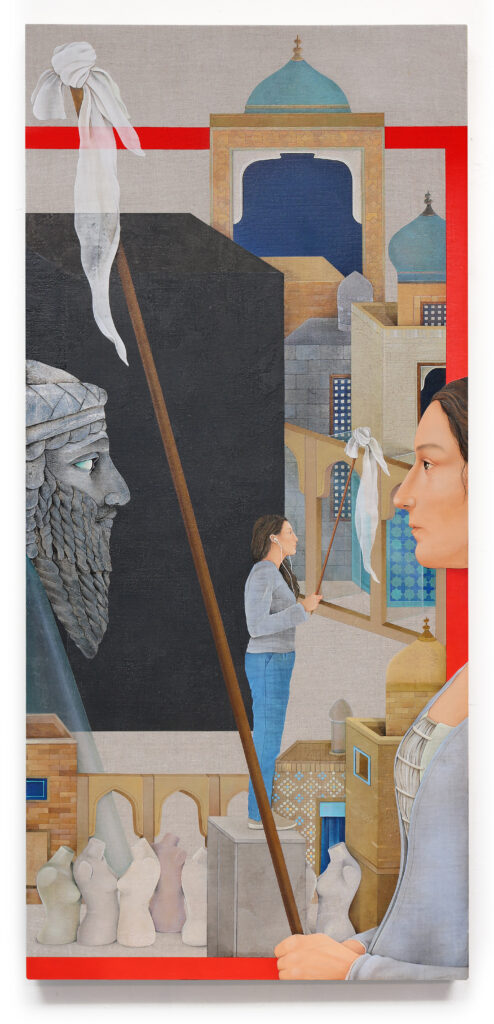

She draws inspiration from a range of sources, including Persian miniature paintings and Renaissance artworks, Greek and Roman sculpture, modern art and fashion photography — and lived experiences and current events. Each work begins with a sketch, where she considers different compositions and elements, including various textures and visual dimensions.

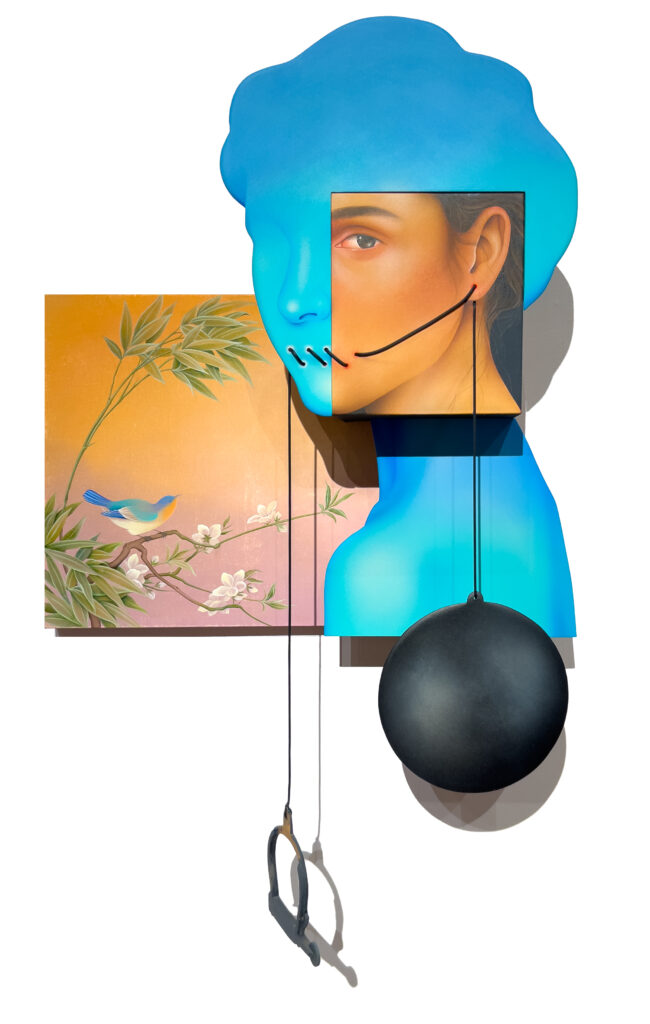

Works on view in Newport incorporate the use of cement and metallics, so the images are at once coarse and shimmering, depending on how and where you look. Some use real textiles and accessories, rugs and belts among them, layered in ways so that the resulting shadows are both two-dimensional and three-dimensional. There is repeated symbolism in the form of birds and flowers, statues whole and broken, limbs and lips more often than entire figures — all framed by unconventionally shaped canvasses that lend the acrylic paintings an air of sculpture.

“I’m the most spontaneous during the sketching part and after that things are very controlled,” Khosravi says. Once she is satisfied with a sketch, she builds the panels in her woodshop.

“[And] once I build the panels, there’s no way to undo things or change my mind,” she adds, noting her work is very planned and precise, and that by the time she begins to paint, she has a “very clear idea of what the painting is going to be.”

In Iran, she worked as a graphic designer for 10 years, mostly doing commercial projects that included logos and poster design, along with branding. She also worked as a children’s book illustrator.

Before she came to the United States to study art, painting was mostly a hobby.

“One year for me was very helpful to transition from graphic design to painting,” she said of her time at Brandeis, where she created a body of work, one she used to apply to grad programs.

She was accepted at the Rhode Island School of Design, and for two years she studied in the painting program. “Eventually, I came up with a creative process, which is evolving ever since, and figured out what I wanted to say in my paintings,” she said.

After graduating from RISD, she was part of an artist’s residency in Provincetown on Cape Cod, which she says was a gift. For seven months, she was able to focus on creating art and not worry about rent or a job. She was also able to be part of a community, something she missed from her time in a school setting. There, she created the body of work that she exhibited in her first New York show.

Khosravi wanted the exhibition at the Newport Art Museum — the title of which bears her name: “Arghavan Khosravi” — to reflect a range of works from different years as well as a variety of her artistic practice, which spans “works on paper to works on textile and then more recent works that have some three-dimensional elements,” she said.

“Currently I’m exploring different scales, but the idea is how I can push the painting towards more three dimensionality, so that the audience can look at them from different angles and there are more layers that will be revealed when you move around the piece.”

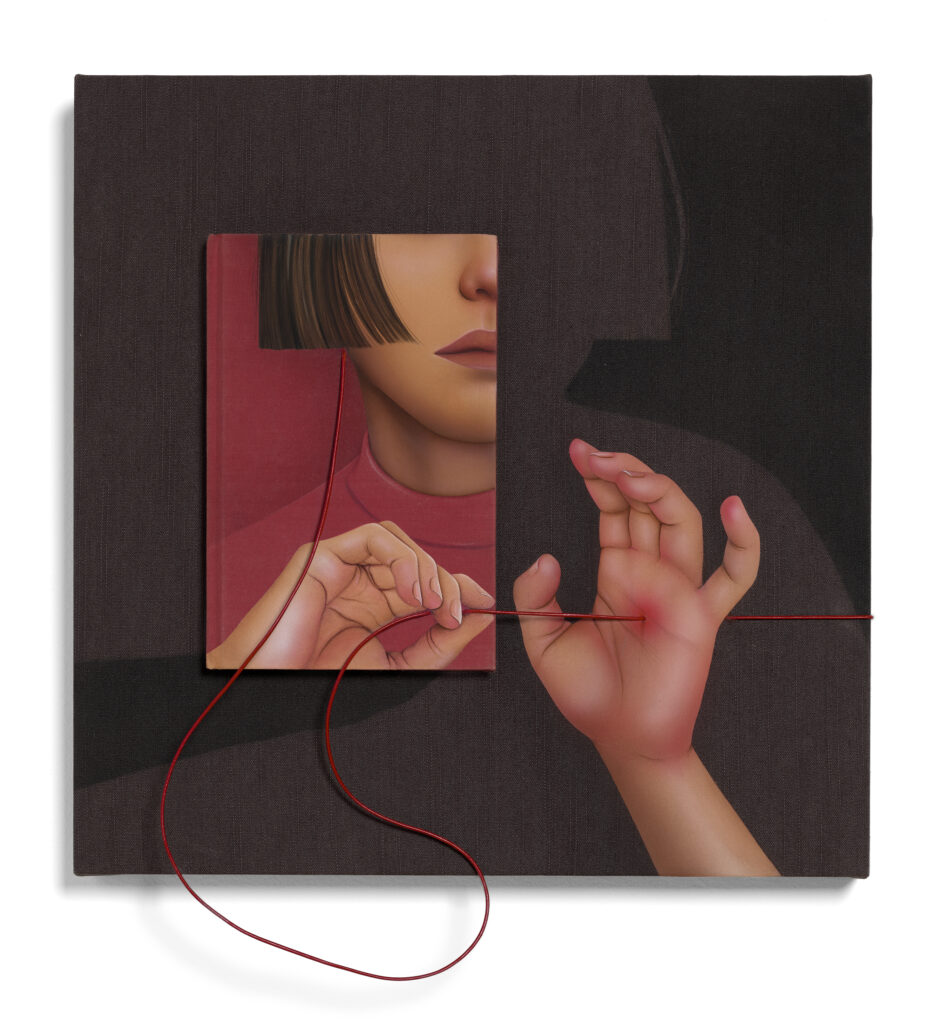

Many of the pieces on view at the museum incorporate a red cord — in the form of a literal string or rope — which weaves through the artwork, often in jarring ways. In two side-by-side pieces, one untitled, a red cord extends from the corner of an eye and to an earlobe, where it takes the form of a headphone wire. In the neighboring work, titled “The Pain,” a red cord extends from just below a woman’s bobbed hairline, taking the shape of a “U” as it moves down and up the canvas, passing through the palm of a hand, and disappearing off the frame. The cord imagery continues to reappear around the room, its endpoints unknown — and conveying a sense of unease.

“Initially I thought of these red lines because I was thinking about my experience from being born and growing up in Iran, and there are a lot of red lines imposed by the government that we mustn’t overpass, so I thought I can have these red lines literally in the paintings, whether it’s painted or actual rope or cords,” Khosravi explained.

In more recent works, she still uses a cord as a symbol, although it appears black and not always red, and has evolved to represent a sort of chain and shackle, sometimes quite literally, as in “The Earring,” which depicts a young woman whose mouth is sewn shut with a black cord, on one end of which hangs a shackle and the other end, which passes through her earlobe, a weighted ball.

Whether black or red, these cords have the same meaning: They are something that prevents the subject from freedom.

Most of Khosravi’s family is still in Iran, including her father, although her siblings have moved to Europe in recent years as “the situation [in Iran] is getting worse and worse.”

Apart from one aunt who has traveled to the U.S., she has not seen any of her family since late 2016, partly because of the Muslim ban imposed by former President Donald Trump in early 2017, which limited travel by people to and from several countries (another theme that has influenced her work), including

Iran, and more recently because of travel restrictions related to her green card.

Now, Khosravi works from a studio at her home in Connecticut, where she lives with her husband. A small loft space on the third floor is her painting studio, and the garage has been converted into a woodshop where she builds all of the panels used to frame her pieces, a part of the process she especially enjoys.

“I like to keep myself challenged in the studio,” she says, adding: “I’m my most creative when I’m in the problem-solving mode.”

As for her work at the museum, which is on view through May 5, 2024, “the starting point is Iran,” she says, and “hopefully it creates a broader conversation around human rights in general.”

RELATED LITERATURE

Newport Art Museum staff put together this list of recommended reading:

- “Persepolis: The Start of a Childhood,” by Marjane Satrapi

- “Women Without Men: A Novel of Modern Iran,” by Shahrnush Parsipur

- “Jewels of Allah: The Untold Story of Women in Iran,” by Nina Ansary

- “Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books,” by Azar Nafisi

- “My Sister, Guard Your Veil; My Brother, Guard Your Eyes: Uncensored Iranian Voices,” edited by Lila Azam Zanganeh

- “The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women,” translated by Dick Davis

- “Sin: Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokhzod,” edited and translated by Sholeh Wolpe

- “I Will Greet the Sun Again,” by Shirin Neshat

- “Art of the Middle East: Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran,” by Saeb Eigner

- “Contemporary Iranian Art: New Perspectives,” by Hamid Keshmirshekan

- “Mostly Miniatures: An Introduction to Persian Painting,” by Oleg Grabar

For more information on the exhibition and any related events, visit newportartmuseum.org. And for more information about the artists, visit her website.

NOTE: pictured at the very top/in the teaser window is Arghavan Khosravi’s “Shouting,” 2021, acrylic on cotton canvas over wood panels. Courtesy of the artist.