A Forgotten Story: The Celestial City-by-the-Sea

By Betsy Sherman Walker

An exhibit at Rosecliff examines the centuries-old relationship between China and Newport — and revisits the notion of East meets West through a 21st century lens.

All images courtesy of the Preservation Society of Newport County

In the upstairs gallery at Rosecliff hang five Chinese lanterns, bold and dramatic. Round and luminous, they are suspended from the ceiling, each bearing images focusing on a chapter in the telling of the Celestial story. There are archival photographs of suffragettes Alva Vanderbilt Belmont and Mabel Lee, Chinese railroad workers in the 1860s, the streets of downtown Newport at the turn of the 20th Century — and even an image of President Lyndon B. Johnson signing into law the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1965.

Contemporary pieces surrounded by mostly historic artifacts, these lanterns were designed by artist Yu-Wen Wu and commissioned by the Preservation Society of Newport County for its latest exhibition, “The Celestial City: Newport and China.“

In Wu’s words, they weave together “themes of migration, exclusion, community, and perseverance,” all of which are central to the show and the stories it offers.

The human side of history

“It was not just about gathering data,” says Nicole Williams, Curator of Collections at the Preservation Society, about curating and developing the story line for “The Celestial City,” a revelatory exhibition on view through Feb. 11, 2024. “The challenge,” she notes, “was how to give back, in color and texture. And

humanity.”

A show that is greater than the sum of its parts, “Celestial City” sets sail with the treasures, lifestyles and family scenarios associated with 19th Century China Trade prosperity and Gilded Age wealth.

Using them as a backdrop, it spins a narrative that includes a misidentified silk and teak room screen, a great-grandmother’s teapot, and archival photographs that tell the barely known history of the Chinese immigrants who made their way to Newport from the California Gold Rush.

Williams began working on the show about a year and a half ago, and says the idea began to percolate prior to her arrival in January 2022. “The Chinese trade was so important to Newport,” Williams said. “I came in knowing this was something I wanted to pursue.”

The exhibit spotlights the centuries-old financial and cultural dynamic between Newport and China. Part history, part social commentary, it relies on the Preservation Society’s collection to underscore the fact that there were not only fortunes to be made in the China trade, but fortunes to be spent. It was a bond founded on commerce, opportunism, an abiding sense of superiority, and fostered by conspicuous consumption.

For context and companionship, Williams reached out in the fall of 2022 to Dr. Bing Huang, an associate professor of art history at Providence College. Last January, Williams enlisted the assistance of research fellow Dani Zhang (a master decoder, in the words of the Preservation Society). “It was a real intercultural

collaboration,” she said.

Many of the items in the show have never been on display before. From the “jam-packed” attics and “obscure dusty corners” of Kingscote to the state archives of the Providence Public Library, Williams, Huang and Zhang spent months uncovering — literally — objects and stories buried, accounts of lives

intertwined, uncovering hidden voices, and hidden heroes.

Williams and Huang, coming at the topic from different perspectives and areas of expertise, nevertheless found a common thread.

Williams’ specialty is American art and the Gilded Age. Huang, a native of Shanghai, specializes in Chinese art and the dynamics of the East Asia and Europe culture exchange. As a teacher, Huang’s goal is to provide her students with context as it relates to the vast arc of Chinese art and the many centuries of its

influence predating the China Trade.

The story within the story

As early as the late 1600s, the more affluent residents of Newport were consumed by what Williams dubbed “the rage for China.” By the mid-1700s, the city “was a bustling seaport in the British Empire connected to China through complex circuits.” Although colonists were forbidden to trade directly with

China, the prized teas, silks, porcelains — even opium — were obtainable through a mixture of piracy and privateering.

The exhibit sets off like a fancy estate sale, along the corridor gallery — with an open invitation from its organizers to question appearances and look for the stories.

On one wall are porcelain plates, teacups and a teapot (circa 1765-1769) that were decorated with scholarly motifs or accented with the — unabashedly American — monograms of the clients. The motifs were based on the works of Chinese scholars, whose more-nuanced messages were lost in translation,

Williams states.

“The plate’s owner [in Newport],” says the accompanying text, “was probably unaware of that meaning and admired the motif as reflecting his own wealth and taste for global goods.”

Kings of the trade

Among the Newport families who made their China Trade fortunes in the 1850s and 1860s were the Kings and Wetmores. Brothers Edward and William King and their nephew David allied themselves with the powerful Canton-based Russell & Co.

From across the divide of nearly three centuries, Williams points out, “It is important to remember, the Kings’ wealth came at a tremendous social and economic cost to China, due to Russell & Co.’s heavy investment in the opium trade.”

The Kings lived for a time in Canton — modern day Guangzhou — and eventually returned to Newport. In 1864, William King bought and updated an 1831 Gothic Revival mansion on Bellevue Avenue and renamed it Kingscote. It remained in the family until 1972, when it was left to the Preservation Society.

On view are the Kings’ lacquered tables and wooden chests, vases, games and chess pieces, letters and documents. A silk-embroidered standing screen (a room divider, Zhang points out, being used as a fire screen), as well as a large painting, circa 1850, of a busy Canton harbor, which was brought from the

library wall at Kingscote.

There are two portraits, also belonging to the Kings, of the merchant Wu Bingjian (known to Westerners as Houma) who invested heavily in the U.S. railroads. According to Huang, Houma was one of the most influential men of his time and thought to be one of the wealthiest.

There is also a portrait of George Washington, circa 1805, done by the Chinese artist Foeiqua, in the style of Rhode Island’s own Gilbert Stuart. A master copier, Foeiqua was so prolific that his “Gilbert Stuarts” flooded the market, prompting the authentic Stuart to seek an injunction against him.

Wetmore and Co. was founded in 1834; the family estate, Chateau-sur-Mer, was built in 1851-1852. Among their treasures are a monogrammed lacquered cigar box, and an early 19th century garden seat from the Wetmore estate in Macao. Also on display is a late 19th-century silk and copper Dragon Robe, which was tied to a member of the royal court prior to the Revolution of 1911.

“After the fall of the Qing dynasty,” viewers are told, “imperial-style garments like this one flooded the Western market.”

At the end of corridor gallery, just beyond the Dragon Robe, is an 1847 Currier and Ives hand-colored lithograph of the royal Chinese junk “Keying.” In 1847 the ship, having made the voyage from Hong Kong via the Cape of Good Hope, sailed in and out of American ports — including Newport — as a museum

ship.

For 25 cents, the curious could go on board for a look-see, visit a small museum with musical instruments and other artifacts (there is a catalog) and observe the Chinese-born seamen as they performed their chores.

Leading ladies

Among the hidden stories was one of Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, considered the most powerful suffragist in her day, who allied herself with a cadre of Chinese-American suffragists. Alva Vanderbilt Belmont was then inspired in turn by a brilliant 16-year-old activist.

A portion of the exhibit is devoted to this history, and Newport in 1912 comes into focus: Alva Vanderbilt Belmont and the woman’s suffrage movement are roiling the social waters of America’s most famous resort. Alva has commissioned the Tea House as a folly-like accent to the magnificent grounds of Marble House, overlooking the Atlantic, and it was often used as a gathering venue for her beloved suffragists. There are watercolors and sketches (some on view for the first time), but that is not the story here.

“This is a story of how Alva intersects with American history and China,” Williams says.

An archive search led her to a 1912 New York Times article about Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, a young Chinese-American activist enrolled in the Barnard College class of 1916. “Mabel and Alva established a relationship,” Williams says. “It was a total reversal of tradition, power dynamic and pattern of influence. Here she is, the most powerful suffragist in the world, listening to a 16-year-old.”

Later, she added, “I began to reframe the Tea House as a monument to change.”

Another prominent figure, New Yorker Grace Yip Typond, was an activist and advocate for Chinese-American women. There are Typond family pictures, but it is the poignant 2023 perspective provided by her great-grandson, Douglas Chu, that resonates.

Chu had no idea his great-grandmother had been a suffragist. “Over time, through family stories and my own research,” he writes, “I have come to appreciate that [my great-grandparents] had something special within each of them.” To hear the news of his great-grandmother, he said, was “surprising,” adding that “the thought of a Chinese immigrant woman deciding to participate in the Suffragette movement

is inspiring.”

Chu made cherished items available for the exhibit, including photographs of his great-grandmother, and he sent along her teapot and teacup — which he explained had long had a special place in the family. “This is the teapot,” he told Williams, “that belonged to my great-grandmother.”

“The teapot,” Williams says, “is my favorite object in the show.”

Collectors or connoisseurs?

Preferring recognition over relevance, one suspects that the Kings, Wetmores, Oelrichs, Vanderbilts and Belmonts would have scarcely given any heed to Williams’ comments about the families being “collectors and not connoisseurs.” They probably would have been more comfortable with Huang, who saw a “backdrop of enduring fascination” in the cultural give and take. Same idea — but from a different point of origin.

“The West and the East are both deeply rooted in history, most vividly manifested in art and artifacts,

meticulously crafted and fervently amassed over the centuries,” Huang said in a conversation with Williams following the September opening of the show.

East met West — in more ways than one — during the telling of these stories. Huang pins the American fascination with China on 18th Century Europeans having recently discovered the 200 B.C. Han Dynasty — and the drive to adopt aspects of the aesthetic as their own.

Where Williams would say that “the spirit of the object was lost when it became a commodity on the open market,” Huang saw “a dance of mutual fascination. Stretching across time,” she adds, “it forms the tapestry of the exhibition.”

Two objects in the show, Huang said, add to that tapestry, and also feeds into the collector vs. connoisseur conundrum. “The phenomenon” of Chinoiserie collected by Americans during the Gilded

Age, Huang says, “prompts a critical inquiry. Is it curiosity in general, or a sensational interest in the strange and shocking?”

The garden seat belonging to the Wetmores and brought to the show from Chateau-sur-Mer tells the classic 13th Century Chinese love story “Romance of the Western Chamber.” The lacquered tables from Kingscote with David King’s monogram (“an exquisite trio”) she says, also bears a cache of hidden — or at least underappreciated — stories.

On the sur face, literally and figuratively, the local scenes (likely of Canton) are set in a hand scroll motif — a traditional Chinese contrivance that suggests there is a deeper narrative beneath the surface, Huang says.

A Chinese community coalesces

Among the tables and teapots there are also examples — disturbing but not surprising — of posters, flyers, and newspaper articles illustrating the racism and discrimination faced by the wave of Chinese immigrants — who came looking for work as laborers in California during the Gold Rush, in the Nevada silver mines and to build the railroads.

“The origin of the family fortune that built Rosecliff,” Williams notes, “was built on the backs of the Chinese laborers.” Tess Oerlich’s father made his fortune in the silver mines of Virginia City, Nevada,

where there was a vibrant Chinese community.

That there was a community of Chinese immigrants who came to Newport was a surprise to just about

everyone. They headed for the cities, in part, to escape the discrimination and prejudice they had endured in the West. They wanted to settle and start anew.

But reading about Gilded Age Newport, “which was home to Irish, Portuguese, Greek, Jewish, and African-heritage Newporters, it seemed like there was a missing story. I knew of Chinatowns in Providence, Boston, and New York forming in the Gilded Age,” Williams explained, “but had not read a word about

a Chinese community in Gilded Age Newport. I thought, ‘there must be a forgotten story here.’”

There was.

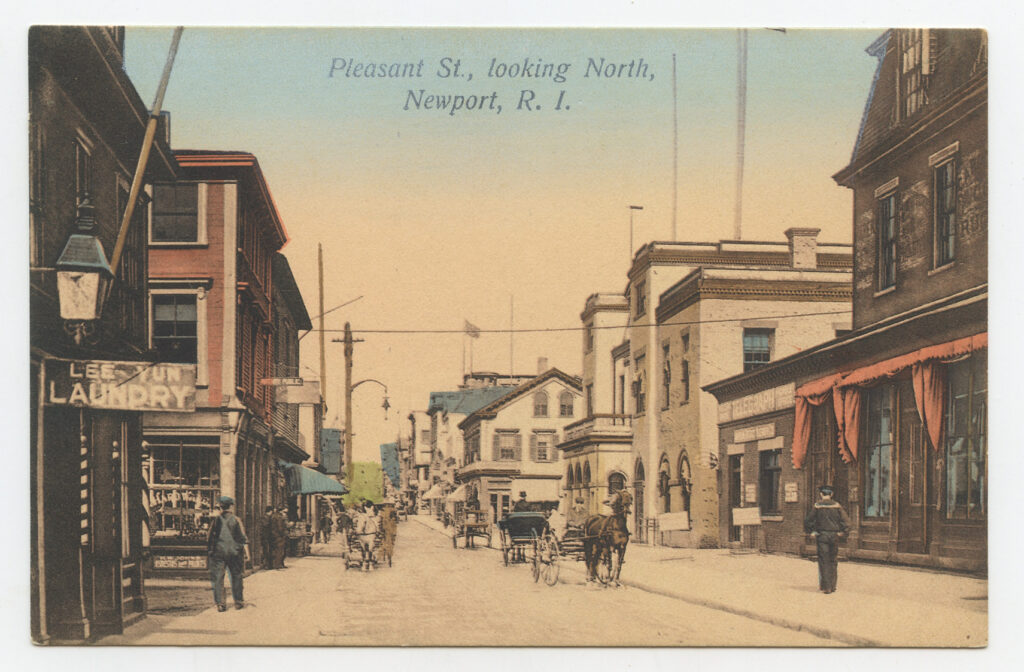

From the archives at the Providence Public Library and the Newport Historical Society, Williams and Zhang unearthed a “massive amount” of Chinese documentation. Photographs documenting the streets of downtown Newport at the turn of the century, when enlarged, showed that there were indeed several Chinese-run businesses, mainly restaurants and laundries. Williams said they found more than 50 Chinese-owned businesses.

They found ads from the Newport Daily News as early as May of 1876, for Wah Sing’s Chinese California Laundry (“plain and fancy work done in best manner”) on the corner of Thames and Green Streets; and for The Oriental Chinese Restaurant on Prospect Hill Street — “The most complete and best-furnished Chinese restaurant in the city” — that offered takeout.

There is a poignant short documentary of the remarkable Gum Lee, a Newport man who was born in China in 1869 and eventually, by way of California, came to Newport in 1901. Gum opened a laundry

on Levin Street the next year; in 1917 he married Mary Crowley, a young woman from Cork, and a year later their son Harry was born. “There was not a lot of intermarriage in 1917,” Williams notes.

From recent interviews with Gum’s grandson, Terrence Lee, we learn more of Gum’s life. The marriage fell apart (Mary was an alcoholic and a wayward mother), and at the age of 12 Harry was placed in a state home, and later moved into foster care.

“The consensus of opinion in Newport,” his caseworker wrote, “is that Lee Gum is not the father of Harry, but that he was always devoted to the child.” The caseworker also mentioned that Harry “was not told in so many words to tell no one that his father was Chinese, but it was hoped that he would show some

[discretion].”

Intercultural collaboration

There is no “best in show” in the exhibition. The Celestial City stories, and the stories within those stories, are all equally compelling.

During one walkthrough, a couple was overheard quietly discussing the show. They were digesting the array of items in the China Trade segment — the grandfather clock, the tables, chests and vases, the portraits, and the stories.

“It’s a long way,” the man said to his companion, “from here to China.”

A long way indeed.

“Our mission was to tell the untold stories, to elevate new voices,” Williams said. “The wall texts are not your typical museum didactic, omniscient voice. Many of them were personalized; many were signed.”

Together she, Huang, and Zhang managed to both elevate and rewrite those stories — and bring the viewer seamlessly into other worlds. Williams was grateful for that collaborative effort — from Zhang’s skill as an interpreter to Huang’s lens — enabling what Bing called the “mystical etherealness intertwined” to rise to the surface.

It was a “real intercultural” collaboration,” Williams said, “The change we want to see in this world.”